Module 3

Essential Questions for this Module

- What happens when a student struggles with reading?

- What is the difference between proficient and non-proficient readers?

- How does text difficulty play a role in this process?

In order to understand why some students struggle, or why some texts may be more difficult than others, we must first understand that success and failure does not solely rest within the reader. In fact there are many factors that contribute to one's learning. In this module, you are presented with a framework for success that includes student ability, text difficulty and instructional approach. Each of these factors are complex within themselves in addition to the interplay among them. Because you will not likely be assigned to teach reading, this module will instead focus on the other factors that play a significant role in learning to read and becoming a proficient reader: text difficulty and student ability.

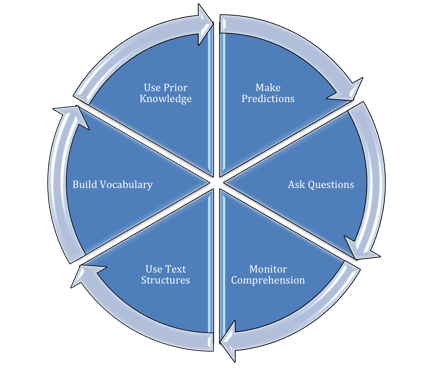

Consider the chart below. These are common characteristics teachers see in proficient readers. Do these sound familiar to you? Do you use these same strategies to make sense of what you read? Chances are you do, but perhaps they are so automatic that you are not aware that you are using them.

In this presentation, you will learn more about what factors contribute to students' success or failure with reading tasks. As you view and listen to this presentation, keep in mind the conditions for learning discussed in module 1 as well as the role of background knowledge for comprehension.

Self-Check. In the activity below, you will sort reader characteristics into those that you would expect to see in proficient readers and those for non-proficient readers.

|

Click the card deck to view a card. Drag the card from the bottom to the correct category. | |

|

||

Defining Text

Defining text is difficult because it is very context specific. We think of text as a placeholder for knowledge. Most people think that text is printed words on a page. However, this is problematic because too many other "texts" without print are meant to be read and interpreted. For example, music, presentations, road signs, videos, and lab demonstrations require students to think, comprehend, and interpret content information.

In order to define text, we must first think about expanding our notions of what a text is. Neilsen (1998) defines text as "anything that provides readers, writers, learners, speakers, and thinkers with the potential to create meaning through language" (as cited in Draper, 2002, p. 523). While this definition, at first glance, seems all-encompassing, a closer look reveals that it still privileges language. Wade and Moje (2000), on the other hand, suggest that texts are "organized networks that people generate or use to make meaning for themselves or for others" (p. 610). This definition opens a path for other modes of communication such as symbols, images, and sounds.

Texts used in schools are varied, and each content area has its own forms of text. Imagine how texts differ from the language arts classroom to the physical education classroom. Both classrooms have specific texts that are unique to their content areas. Every 50 minutes, students must adjust to different texts as they move from one subject area to another. While learners process all of the texts in similar ways (i.e. activating schema, decoding the message, and comprehending), there are nuanced differences in what students will need to interpret the texts. Teachers should support students while they use these texts for learning. Therefore, teachers must know what form the texts take in their subject area.

Structure

Text characteristics are multifaceted and are dependent on format and genre. Traditional printed textbooks, for example, typically contain a table of contents, a glossary, an index, and pictures with captions to illustrate concepts. Non-traditional texts like videos, songs, task cards, graphs, and websites contain their own unique structure and set of characteristics. Assessing a text's characteristics means that you will want to think about how the structure and features support or create a barrier for students' learning. Where will you need to supplement information? What do you want students to pay more or less attention to? What will you need to explain prior to students' encounter with this text?

In this presentation, you will learn more about specific text structures within various content areas, and why some students may struggle depending on the text demands.

Author Assumptions

Just because a text seems to fit within a particular subject of study does not mean that it is the best text to use. We must also consider the match between the text and the students.

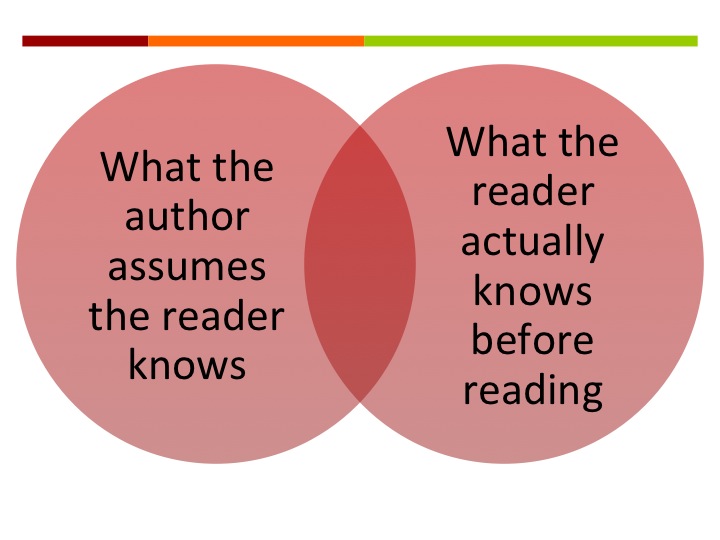

When authors are writing a text, they typically write to an implied audience. This implied audience is based on the author's assumption about who will be reading the text, or the intended reader. For example, if an author is working on a 9th grade science textbook, he or she must make assumptions about the background knowledge of a typical 9th grade student. Additionally, to make the textbook more marketable, the author has to consider what is typical background knowledge for 9th grade students across the nation. As you might imagine, this is essentially an impossible task. First, background knowledge is both what students learned in science prior to 9th grade but also everything they have learned outside of school. Since students' interests vary considerably, what is learned in and out of school for any two students will be different. How might an author account for this variability for all students who will come into contact with this text? The author uses an implied reader, and the author decides what an average 9th grader should know.

The following diagram (adapted from McKenna, Robinson, 2008) presents a framework for thinking about how your instruction fits within the author's assumptions and your students' prior knowledge.

To determine what an author has assumed about his/her readers, teachers can take the following steps (adapted from McKenna and Robinson, 2008):

- Look for references to previous material.

- Examine the new vocabulary necessary for comprehension.

- Determine which words or images must be known in advance in order to make sense of them.

- Look for references that are not adequately explained.

- Consider the relevancy of the content to students' lives.

- Evaluate the familiarity with task/text demands or format.

These steps can be applied to any text regardless of its format.

Although many schools use a set curriculum and a designated textbook (or set of texts) for each grade level, these texts are almost never a good match for all the students in a classroom. Motivation and interest in the reading material aside, most of these texts will either be too difficult or too easy for several of the students. The cause of this mismatch is often related to the previous knowledge each individual brings to the text. Teachers have to think about the texts they use and assess their match with readers in various ways. The following characteristics should be considered when selecting a text for instruction, whether that text is print or non-print: quality, structure, author assumptions, readability, and features. In addition to these characteristics, teachers will also need to know (1) how the text matches the purpose, (2) the students' needs, interests, and prior knowledge, and (3) the content standards that must meet.